JANA G. PRUDEN

PUBLISHED MARCH 5, 2024, BY THE GLOBE AND MAIL

In the 19th century, Kit Coleman, Sara Jeannette Duncan and Faith Fenton pioneered women’s journalism at the newspapers that would evolve into The Globe and Mail of today.

The legion of newspapermen covering the Spanish-American War in June, 1898, received some shocking news. A reporter was arriving by train to join the 150 or so other correspondents gathered in Tampa, and she had official papers from the U.S. War Department.

“A lady war correspondent!” wrote Charles E. Hands, one of the newsmen reporting on Cuba that summer. “The idea was too comic. We could not believe it. … After all, we said, there were limits of the sphere of women’s usefulness.”

His story about the new reporter’s arrival ran under the headline: “Mrs. Blake Watkins, Lady War Correspondent.”

Kathleen Blake Watkins – who would in a few months become Kathleen Blake Coleman, after her third marriage – was better known to newspaper readers in Canada as “Kit of the Mail,” a beloved columnist at one of the publications that would become today’s Globe and Mail.

Coleman was part of a rising tide of women boldly breaking into pages that, until then, had been seen as a man’s domain.

Disgruntled newsmen aside, journalism was changing. Newspapers of the day were loosening their connection to political parties and becoming more independent business operations funded with advertising dollars.

At the same time, the place of women in society was evolving, and editors had indeed begun to see the “usefulness” – or at least the potential revenue – to be had from women reporters writing for women readers.

“This was a period in which there was more and more emphasis on trying to make the newspaper appealing to women, because advertisers realized that women were spending a good portion of the domestic dollar,” says Misao Dean, a specialist in 19th-century Canadian women writers. “They were creating features and columns specifically for women readers, and this was going to get them more advertising dollars.”

Women’s pages also came about at a time when there was increasing awareness of what women writers could contribute to society more broadly. On pages and in columns such as “Woman’s World” at The Globe and “Women’s Empire” at The Empire, female writers were tasked with producing “articles of interest to women” – or at least the things male editors thought women wanted to read.

“There was grudging appreciation of their intelligence and their worldview as being somewhat different from a male view,” says Barbara Freeman, an adjunct research professor in the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University. “And maybe something worth considering from time to time.

In Canada, Kit Coleman of The Mail, Sara Jeannette Duncan of The Globe, and Faith Fenton of The Empire (all predecessors of The Globe and Mail) pioneered the place of women on the page, waging their own battles for respect, ink and the opportunity to write about more than the latest styles of hats – as glorious as the hats of the day may have been.

“Kit hated covering fashion, but twice a year, at least, she had to go down to the department stores and write up all the fashions,” says Freeman, author of Kit’s Kingdom: The Journalism of Kathleen Blake Coleman. “She always said that women should be able to write about politics and business.”

It seems Hands would come to agree. Despite his early misgivings about Coleman’s arrival in Tampa, he would, by the end of his story about her, admire her chops as a journalist and commend her ability to be “one of the boys.”

Jill Downie, author of A Passionate Pen: The Life and Times of Faith Fenton, says it can be easy to forget the controls that existed on women’s lives at the time and, in that environment, how truly revolutionary women in the reporting ranks would have been. She notes that women faced restrictions on what they wore, where they went and how they lived – with marriage still considered to be the ultimate goal. “Thinking outside that tiny little box was a very dangerous thing to do,” she says.

Downie says the women’s pages, sometimes known as the “lace-collar ghetto,” was a section of the paper where women became trapped writing about domestic subjects, and had limited opportunities to do serious work.

But there were great possibilities to be found in the women’s pages, too. Serious and even subversive matters were being addressed alongside – or even within – columns about cooking, gardening, social happenings and fashion, right under the noses of the men running the paper, or husbands leaning in for a look.

One Globe women’s page from 1885 includes a story about dressing little dogs in fancy attire; instructions on how to make coffee syrup; tips on cleaning rooms where someone has been sick; a story about suffrage in the United States and why women should vote; an analysis of the wardrobe of a famous actress; much news about hats; an encouragement to women to try outdoor activities, including cycling; and an anecdote about a tall and “majestic-looking” female rancher travelling with her female companion to a cattle show, in which the rancher is quoted saying: “Men are all frauds. I wouldn’t marry the best one of them that ever lived.”

Dean says The Globe’s Duncan had an editor who allowed her to write what she wanted in her column, and “she went for it,” even writing on suffrage about 40 years before most women got the vote. “I think in these articles about appearance or about fashion, she was trying to suggest to women that many of the standards of beauty were themselves oppressive, and were reinforcing more serious limitations on women’s lives,” says Dean, who has written extensively about Duncan’s journalism and works of fiction.

When her male editor passed along a letter from a female reader asking for a household beauty remedy for freckles, Duncan made it clear in her response she had no such advice to give, and instead questioned why the woman would want to get rid of them at all. “Don’t you know that Cleopatra was freckled? … I like to think of you there against the sunset, with your bare arms akimbo on the gate, freckles and all,” she wrote.

But her perspectives were daring, even revolutionary, and there was no small degree of pushback. As Fenton wrote in The Empire in 1891, after a reader raised the idea of a women’s column that could be written without any restrictions: “I pictured the face of the managing editor were I to go to him with a request for such a column. Visions of woman suffrage, communism, libel suits and general anarchy would flit before him in swift succession.”

Fenton understood that women themselves were still coming to terms with such bold ideas. She wrote in 1895 that it was hard for the average Canadian woman “to loosen the old conventionalities, the old-time proprieties and properness in which men have so carefully swaddled her.”

It may be for this reason that Fenton’s most subversive columns begin softly, using what Downie calls “her comfort words,” asking whether women should be able to vote, to belong to certain clubs, to go out without male escorts. “She’s trying to coax women that these are not dangerous thoughts,” Downie says. “She’s saying, ‘It’s safe to think like this. It’s interesting to think like this.’”

But while she wrote of women’s liberation, Fenton herself lived a double life for 19 years. By day, she was a spinster teacher under her real name Alice Freeman, and by night, Fenton, the popular newspaper writer. Downie says having two jobs was financially necessary because her salaries as a journalist and a teacher were less than half what her male colleagues made. The secrecy was similarly required because Fenton would have been fired from her teaching job had it been revealed that she was also writing for the newspaper.

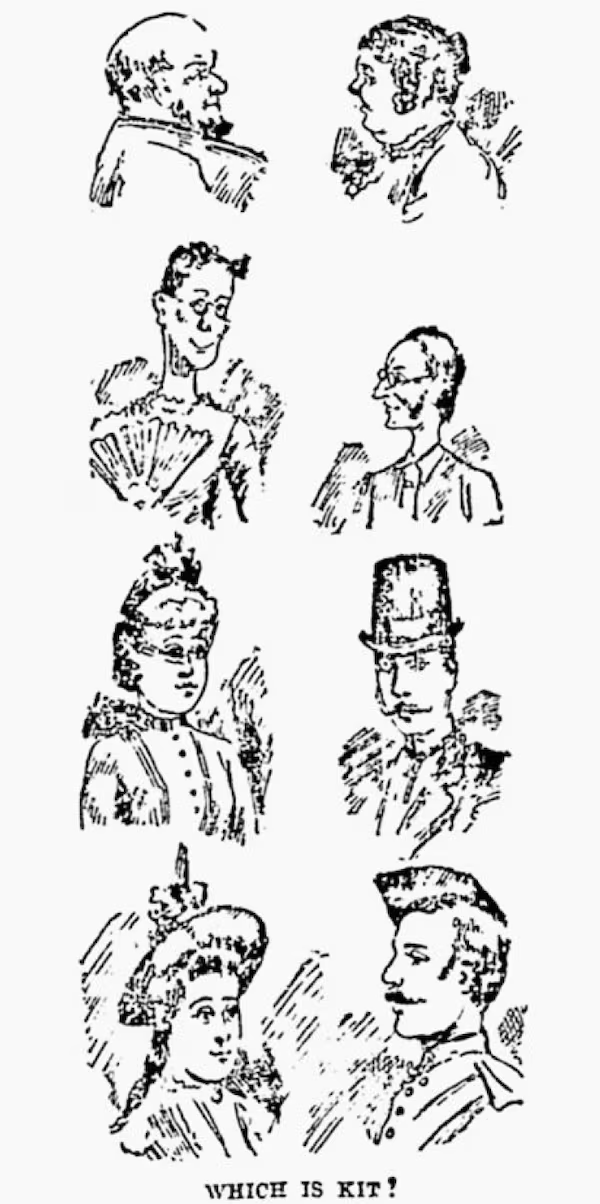

This split between a woman’s work and personal life wasn’t unusual for the time. Coleman’s identity was so mysterious that debate raged in the papers over who she was, and, in 1890, The Globe ran a series of drawings asking, “Which is Kit?” – imagining who the real Kit of the Mail might be. Four of the eight images were men.

Globe readers in 1890 were invited to guess which of these people resembled the real Kit Coleman.

Freeman, the Carleton University professor, says Coleman had “a bit of the Irish blarney in her,” and enjoyed the speculation about her age, appearance and gender. The differences between the woman and her byline were so stark that Freeman writes about her as two different characters: Kathleen in real life, Kit on the page.

Other female reporters in Canada, such as Vic Steinberg of the Toronto News, used male bylines and regularly went undercover as men to experience and report on things they couldn’t have access to otherwise.

Duncan began her career writing under the name Garth, and later, Garth Grafton. Though it was apparent in her articles that she was female – she writes, for instance, about being a woman attempting to buy insurance for herself – the masculine pen name suited the convention of the time, even if readers knew the author was female. Dean says Duncan could be “quite snippy” about what she thought of as excessively feminine or frivolous pen names for women. “She took herself very seriously as a journalist,” says Dean.

Although being a woman was a serious impediment in some ways, it also provided perspective and access that male reporters didn’t have, such as when Fenton visited women’s prisons, so “readers of the Empire might know something of the daily lives of those restless, broken-winged birds, the imprisoned women of Ontario.”

When Coleman was being dispatched to cover the war in Cuba, a story in The Catholic Register noted that being a woman among the nurses, “she will be in a position to gain information of intense interest about the hospital service such as no male war correspondent has ever yet been able to gather on the field at first hand.”

Still, Coleman wrote that she was “very keenly made to feel her inferiority” by some men of the press, who harassed her and tried to prevent her from doing her work, and that military generals brushed her away “as though I were an impertinent fly.”

As one of two women covering Parliament while writing for The Washington Post, Duncan described an environment of choking cigar smoke, blue language and hostility that drove the women out of the press pool and into the library instead. She left Canada in 1888 to tour the world with another female journalist, and married a man in India, moving away from journalism to become an accomplished fiction writer.

At the same time Coleman was breaking out of the women’s pages to cover the war in Cuba, Fenton – then 40 years old, unmarried and laid off during the merger of The Mail and The Empire in 1895 – journeyed to Yukon with a group from the Victorian Order of Nurses and became The Globe’s correspondent in the Klondike. It was a period that would come to define her journalistic career, and in which she witnessed and covered serious, front-page news. That came to an end when she met a doctor and became “Mrs. John N. E. Brown,” leaving her career as a journalist to, as she described it, be “the wife of her husband.”

Coleman continued to write for newspapers and magazines until her death in 1915. Her final column, which ran a month before she died, talked about the babies fathered by soldiers overseas, describing the children as: “The cruel outcome of our nonsensical wars, our absurd and shocking ‘civilization,’ our conventional mock modesty.”

News of Kit Coleman’s death made the front page of The Globe on May 17, 1915, sandwiched

between dispatches on the war in Europe, the subject of her final column.

The women’s reporting – informed by their past experiences, and also by the time in which they lived – was not without its flaws. There are, in places, inaccuracies, insensitivities and patronizing attitudes. But while Dean says it’s easy to either dismiss or excuse these writers, the reality is more complicated. “They were all individuals, and some of them were more progressive than we might expect,” she says. “It’s only by studying them in their historical context that we can come to understand how they represent the roots of our own ideas and prejudices.”

Downie describes the early women reporters as “imperfect people who needed to make a living and managed to carve out an increasing role for women in the newspaper industry, despite continuing limitations because of their gender.” She says examining the women’s views and writing in the context of their time also gives a clear picture of how the present world has advanced and changed. “One cannot rectify or justify,” she says. “One can only try to understand and explain the world she lived in.”

In that restrictive world, the pioneering newspaperwomen of The Globe, The Mail and The Empire led serious and groundbreaking public discussions about issues such as spousal abuse, pay equity, poverty and women’s independence, which would ignite the women’s movement in the century to come.

The long-term impact of this early journalism by women is impossible to measure, but Downie recalls a story shared by a young woman after Fenton’s death in 1936 that may give us a glimpse. The woman described her mother showing her a photo of Fenton journeying to the Klondike, part of “a human chain of persons going up an icy slope to a terrifying path between mountains, people looking like tiny black dots in the formidable scene.”

“She remembered her mother saying, ‘One of those tiny black specks is Faith,’” Downie says. “So there’s a little girl being shown that picture of Faith Fenton the journalist doing this, and her mind will never be the same again. She will never think along the same lines. I would like to think that was the influence she had on a generation of women.”

Their work didn’t change everything – women journalists would continue to face serious hostility and prejudice on the job – but Dean says it helped create a market for women’s voices, and a place for women who said what they thought and who were direct about it. Because of that, she says, “It became less and less possible for newspapers to keep them out.”

Coleman was the founding president of the Canadian Women’s Press Club, formed in 1904 so female journalists barred from male press organizations could meet and support each other. There, the young women reporters gathered around Coleman, who encouraged them in their work and urged them to keep going in their careers, even when it was difficult.

“They really looked up to her, and they, in turn, did their best,” Dean says. “And that whole generation inspired the next generation, which inspired the next generation.”

In 2023, the Royal Canadian Mint issued two collector coins in Kit Coleman's honour, making her the first female journalist to appear on a Canadian coin. Special edition coin mint.ca.

In 2023, the Royal Canadian Mint issued two collector coins in Kit Coleman's honour, making her the first female journalist to appear on a Canadian coin. Special edition coin mint.ca.

Navigating male-dominated newsrooms herself in the 1970s, Freeman says the example set by persevering female journalists such as Coleman continued to help set the course for the women who followed.

“If we have so many women in journalism today, it goes back over 100 years, 120 years, to when these women started out,” she says. “It was really due to them, because they kept trying.”

Jana G. Pruden is a feature writer at The Globe and Mail, based in Edmonton.

This is an excerpt from A Nation’s Paper: The Globe and Mail in the Life of Canada, a collection of history essays from Globe writers past and present, coming this fall from Signal/McClelland & Stewart.

© Copyright 2024 The Globe and Mail Inc. All Rights Reserved. globeandmail.com and The Globe and Mail are divisions of The Globe and Mail Inc., The Globe and Mail Centre 351 King Street East, Suite 1600 Toronto, ON M5A 0N19 Andrew Saunders, President and CEO.