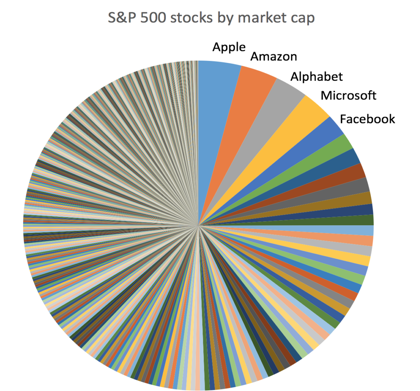

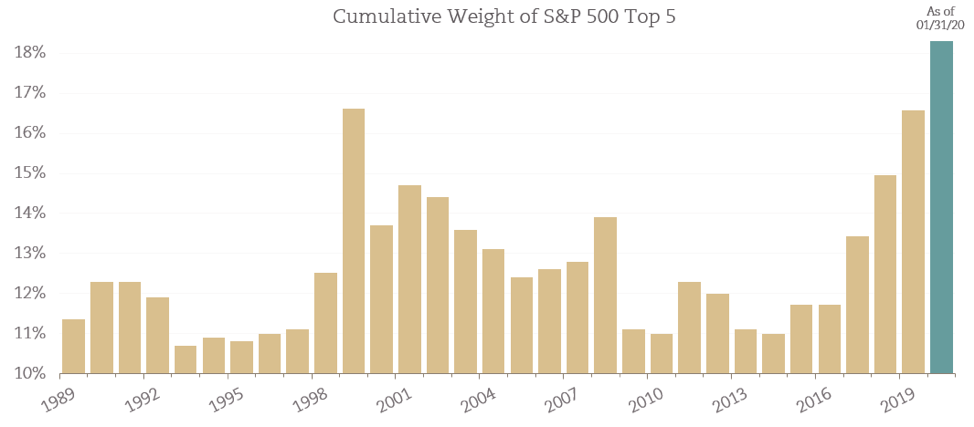

As we begin a new decade, one can’t help but note the extreme concentration in the S&P 500, an index that is supposed to be a broad representation of the US market. Currently, the five largest companies in the S&P 500 account for roughly 18% of the market value of the entire index. To put that into perspective, both Apple and Microsoft are now worth more than the entire S&P 500 energy sector.

“Each era produces its own set of market beliefs.”

Sharon Watkins, OUTLOOK 2020

Each investment cycle begins with the belief that the current market environment will carry on for the foreseeable future. However, as history shows, we are human and quite predictable. Each era produces its own set of market beliefs. Let’s look at the previous investment cycles and the core beliefs of its time.

- The 1970s saw ‘peak oil’ and a conviction that inflation would never die, while the 1980s saw the opposite.

- The 1980s brought a view that Japan would take over the world, yet the 1990s told a different story.

- The 1990s was technology should be valued differently - we all know how that turned out.

- The 2000s was the obsession with China’s ‘growth at any cost’, leading to underperformance in the 2010s.

Where are we now?

The 2010s were a period of massive dominance by a few “mega tech” stocks, primarily the FANGMA (Facebook, Apple, Netflix, Google, Microsoft, Amazon). These companies have captured significant power and influence over the world. MAGA isn’t about ‘Make America Great Again,’ it’s about Microsoft, Amazon, Google and Apple each being worth over $1 trillion dollars. Yes, that’s TRILLION, with a T! These mega tech firms have been the leaders in this record-long bull market with superior growth and dominant market share in their respective industries. And that brings us to today where the S&P 500 is more concentrated than at any other time in history.

Can this last forever?

What has happened historically when a handful of companies dominated such a large percentage of the market?

When companies become monopolistic (a concentration in power) they squash innovation, gobble up the competition, and create significant barriers to entry. This has been exacerbated by passive investing. Twenty cents of every dollar invested in an Index ETF is allocated to the top 5 companies, further increasing their weight. Thus, performance is more pronounced on the way up… and on the way down. As history has repeatedly shown, past performance is not indicative of future gains.

Currently, there are over 16 active anti-trust investigations into the aforementioned companies. Anti-trust is something that we have seen before – remember the early 1980s? The US government ended Telecom’s dominant status breaking up AT&T into eight different companies; known as the baby bells. This Bell System break-up created a more competitive environment that led to new technologies, companies, platforms and business models. And for the consumer, the result was lower prices and improved service quality.

Historically, is it best to own the biggest companies?

From 1972 to 2013 the S&P 500 was up close to 5,000% but if you owned just the biggest stock in the index every year you would have only gained around 400%. The biggest gains are from recognizing a new trend early and investing on the way to the top spot, not once a company already makes it there.

Other Historical Notables: General Electric had one of the best runs holding a spot in the top 10 in the S&P 500 from 1980-2015. But nothing lasts forever and GE isn’t on the list today. Other stocks that appeared on the S&P 500 top 10 list over the years and have fallen on hard times include Sears, Kodak, General Motors, Ford Motor, America Online and Bank of America.

Bottom Line

With the market at record concentration levels, the business models that are expected to dominate the world forever are beginning to show some cracks. Last year, while Apple’s share price rose over 86%, it’s revenue was down 2% and gross profit fell 3.4%. This isn’t to say these are not great companies but, rather, don’t get caught in a good company/bad stock scenario. Working off excesses are healthy and quite normal. If there is one thing to remember, remember this: it's what you pay!

“What a wise man does in the beginning, the fool does in the end.”

Howards Mark